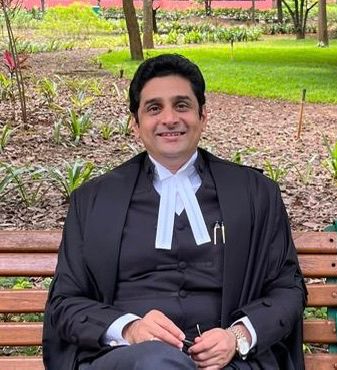

Justice (Rtd) Anand Byra Reddy.

This is a brief compilation, on how the 'Group of Companies' doctrine is relevant in the context of Section 8 and Section 1 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 ('A &C Act', for brevity). The same is sought to be addressed with reference to the factual matrix of an arbitration case.

2. An arbitration claim was brought by a real estate company against two respondents. The first respondent, ('R-1', for brevity) an individual, was said to have represented to the Claimant, that he was the agreement holder, to purchase several items of land, belonging to various landowners of a village near Bengaluru. The said items of land were said to form a compact and a contiguous block of about 45 acres of land. The price of the above lands was said to have been agreed to be at Rs.4 Crore- per acre. The transaction related to two parcels of land, a smaller extent - to provide access from a main road and to provide frontage to the development proposed in the larger extent, both sets of lands together measuring as above.

3. The Claimant company and R1, the agreement holder, are said to have executed a document styled as a 'Memorandum of Understanding' ('MoU', for brevity). It was said to have been agreed in terms of the MoU, that R-1 would convey and ensure the conveyance of all the lands mentioned above, to the Claimant. However, after receiving a nominal advance, from the claimant to take the transactions forward, R-1 is said to have played truant for a considerable time. The above said MoU also is said to have contained an arbitration clause - which provided for resolution of disputes, if any, between the parties..

4. At the above juncture it was said to have been learnt, by the Claimant, that some of the above items of land were being transacted for sale, by some of the landowners with a third-party, in respect of which there was said to be a newspaper publication - which is said to have c o m e to the notice of the Claimant and p r o m p t e d it to immediately launch proceedings against R-1. And the Claimant is said to have secured an Order of injunction under Section 9 of the A&C Act from a competent civil court, against R-1, or anybody acting under him, from alienating or encumbering the properties described in the Section 9 petition.

4. Simultaneously, with the above, the Claimant is also said to have approached the High Court with a petition under Section 1 of the A & C Act, seeking the appointment of an arbitrator to adjudicate the dispute that was sought to be raised. The said petition was said to have been allowed and an arbitrator appointed. Significantly, the proposed third-party purchaser of the above-mentioned lands, was not made a party - either before the civil court or the High Court, in the proceedings instituted as above, by the Claimant company - against R-1.

5. The Claimant is said to have then filed the arbitration claim against R-1 and against R-2, naming R-2 as a respondent to the dispute - for the first time - before the Arbitrator. R-2 was said to be a limited liability partnership, registered under the Limited Liability Partnership Act, 2008. R-2 is said to have raised a preliminary objection of misjoinder. It was said to be contended by R-2 that it was not a party to any agreement with the Claimant and that it was not a party to any proceedings instituted against R-1 by the Claimant, either in the Application under Section 9 of the A & C Act, before the trial court or in the petition under Section 11 of the A & C Act, before the High Court and hence, could not be impleaded in the arbitration.

6. R-2 is said to have also contended that, though it was possible to implead a party to an arbitration proceeding for the first time, even without being impleaded in any proceedings preceding the arbitration, yet - a notice under Section 21 of the Act was mandatory. For, it was contended, there was no privity of contract between the Claimant and itself..

7. The law of joinder of non-signatory parties, in arbitration, has evolved substantially. The judgment of the Supreme Court of India in the case of Chloro Controls India (P) Limited v. Severn Trent Water Purification Inc., (2013) 1 SCC 641, was a turning point. Hence, the law as it stood Pre-Chloro Controls and Post-Chloro Controls, as summarised below, may be kept in view. It may also be noted that Chloro Controls, was a decision rendered in the context of Section 45 of the A & C Act, relating to enforcement of a foreign Award and Part Il of the said Act.

The Pre-Chloro Controls legal position:

(i) Arbitration could be invoked at the instance of a signatory to the arbitration agreement only in respect of disputes with another signatory party.

(ii) The court would adopt a strict interpretation of the provisions of the Arbitration Act, particularly Section 8 of the A & C Act, before its amendment, which only allowed reference of 'parties' to an arbitration agreement.

(iii) There was an emphasis on formal consent of the parties, thereby excluding any scope for implied consent of the non-signatory to be bound by an arbitration agreement.

The Post-Chloro Controls legal position:

The apex court had, in interpreting the language of Section 45, held that the expression 'any person', reflects a legislative intent of enlarging the scope beyond 'parties', who are signatories to the arbitration agreement, to include non-signatories.

The Court held that a non-signatory could be subjected to arbitration 'without c o n s e n t ' in 'exceptional cases' based on four determinative factors:

(i) A direct relationship to the party which is a signatory to the arbitration agreement

(ii) A direct commonality of the subject-matter and the agreement between the parties being a composite transaction.

(iii) A direct commonality of the subject-matter and the agreement between the parties being a composite transaction.

(iv) The transaction being of a composite nature where performance of the main agreement may not be feasible without the aid, execution, and performance of supplementary or ancillary agreements for achieving the common object and collectively have a bearing on the dispute; and

(iv) A composite reference of such parties will serve the ends of justice.

8. The Development Post-Chloro Control:

Pursuant to the Chloro Controls judgment, the Law Commission of India, in its 246th Report (2014), recommended a m e n d m e n t s to the A & C Act. The Commission observed that the phrase 'claiming through or under' used and understood in Section 45 of the Act, was absent in the corresponding provisions of Section 8 of the Act. It was suggested that the definition of 'party 'under Section 2(1) (h) be amended to also include the expression 'a person claiming through or under such party'. The legislature amended Section 8 to bring it in line with Section 45 of the Act by the 2015 Amendment Act. Though the amended Section 8(1) provided that 'a party to an arbitration agreement or any person claiming through or under him' could seek a reference to arbitration. However, the legislature did not make any change in the language of Section 2(1) (h) or Section 7 of the Act.

9. After the Chloro Controls judgment and after the amendment to Section 8 of the Act, several decisions of the Apex Court discussed the Group of Companies doctrine, to join the non-signatory persons, or entities, to arbitration agreements, namely, in the following:

a. Cheran Properties v. Kasturi a n d Sons Ltd., (2018) 16 SCC 413;

b. Ameet Lalchand Shah v. Rishab Enterprises, (2018) 15 SCC 678;

c. Reckitt Benckiser (India) Private Limited v. Reynders Label Printing India Private Limited, (2019) 7 SCC 62;

d. Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. v. Canara Bank, (2020) 12 SCC 767; and

e. Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd. v. Discovery Enterprises, (2022) 8 SCC 42.

10. A Constitutional Bench of the Apex Court, in the case of Cox & Kings Ltd. v. SAP India (P) Ltd., (2024) 4 SCC 1, has addressed the above cases to expound on the developments post - Chloro Controls judgment. Incidentally, the following questions were referred to the above said larger Bench by a 3-judge Bench of the Apex Court, which had doubted the correctness of the application of the Group of Companies Doctrine by the Indian Courts and the reference was on the following questions:

a. Whether the phrase 'claiming through or under' in Section 8 and 11 could be interpreted to include the 'Group of Companies' doctrine; and

b. Whether the 'Group of Companies' doctrine as expounded by Chloro Controls

case (supra) and subsequent judgments, is valid in law.

In a concurring opinion, one of the Hon. Judges on the Bench, while expressing that the Apex court, in its earlier decisions, had adopted inconsistent approaches while applying the doctrine in India, that needed clarification, and accordingly, highlighted the following additional questions of law for determination by the larger Bench:

c. Whether the Group of Companies Doctrine should be read into Section 8 of the Act or whether it c a n exist in Indian jurisprudence independent of any statutory provision;

d. Whether the Group of Companies Doctrine should continue to be invoked on the basis of t h e principle of 'single e c o n o m i c reality';

e. Whether the Group of C o m p a n i e s Doctrine s h o u l d b e c o n s t r u e d a s a m e a n s of interpreting implied consent or intent to arbitrate between the parties; and

f. Whether the principles of alter ego and/or piercing the corporate can alone justify pressing the Group of Companies Doctrine into operation even in the absence of implied consent.

11. The Constitution Bench, before addressing the earlier decisions of the Apex Court, referred to above - on the point, took note of the development of the doctrine, at paragraphs No.39 - 45, of its Judgment, to state that the Group of Companies Doctrine in arbitration law mainly originated from the decisions of international arbitral tribunals, more particularly in a case decided by an ICC tribunal, in a case - popularly known as the Dow Chemicals Case. (Dow Chemicals v. Isover Saint Gobain, Interim Award, ICC Case No. 4131, 21.09. 1982)

12. The facts of the Dow Chemicals case is briefly narrated by the Apex Court, at paragraphs No.40 - 44 of the above judgment, thus:

Dow Chemicals (Venezuela), had entered into a contract with a French company, which later assigned the rights to /sover Saint Gobain for distribution of the thermal insulation products in France. Dow Chemicals (Venezuela) subsequently assigned the contract to Dow Chemicals AG, which was a subsidiary of Dow Chemicals Company - the holding company. Thereafter, Dow Chemicals Europe, a subsidiary of Dow Chemicals AG, entered into a similar contract with three companies, which subsequently assigned the contract to sover Saint Gobain. Both contracts provided that the deliveries of products to the distributors will be made by Dow Chemicals France, or any other subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company. Several suits were instituted against the companies of the Dow Chemical group before the French courts. In response, the four companies of Dow Chemical group (the two formal parties to the contract - Dow Chemicals AG and Dow Chemicals Europe, and the two non-signatories - Dow Chemical Company and Dow Chemicals France) instituted arbitral proceedings against /sover Saint Gobain before the ICC tribunal.

The primary issue before the ICC tribunal was to determine its own jurisdiction over the non- signatory parties. The tribunal sought to determine whether there existed a common thread of the parties to be bound by the arbitration agreement. The tribunal established the common intention of the parties by analysing factual circumstances underpinning the negotiation, performance, and the termination of the contracts. The tribunal held that Dow Chemicals France "was a party" to the two contracts, and consequently to the arbitration agreements contained in them, because it played a preponderant role in the negotiation, performance, and termination of the contract. As for Dow Chemical Company, the tribunal held that the holding company h a d ownership of the trademarks under which the products were marketed in France and had absolute control over its subsidiaries who were involved in the negotiation, performance a n d termination of the contracts. The tribunal also relied on the fact that Isover Saint Gobain applied for the joinder of the holding company into the court proceedings in France before the Court of Appeal of Paris.

After concluding that the non-signatories were also a party to the arbitration agreement, the tribunal proceeded to analyse the factual circumstances of the signatory and non-signatory belonging to the same group of companies. At the outset, the tribunal observed that a group of companies constitutes one and same economic reality. However, the tribunal emphasized that a non-signatory may be bound by the arbitration agreement entered into by another entity of the same group if the non-signatory appeared to be a veritable party to the contracts on the basis of the involvement in the negotiation, performance and termination of the contracts. The Dow Chemicals c a s e h a s b e e n r e g a r d e d a s being i n s t r u m e n t a l in the transition from a restrictive interpretation of consent focusing only on its express manifestation to a more flexible approach attaching necessary relevance to implied consent to be bound by the arbitration agreement.

In a series of subsequent rulings, the Court of Appeal of Paris acknowledged the extension of an arbitration agreement to non-signatories provided there was common intention of all the parties. According to the Court of Appeal, the common intention may be ascertained from the active role played by the non-signatories in the performance of the contract containing the arbitration agreement which gives rise to the presumption that the non-signatory had knowledge of the arbitration agreement.

13. In narrating the summary of the Dow Chemicals case, as above, the Apex Court has reflected on the several of its own decided cases, in India, post- Chloro Controls case, namely:

Cheran Properties supra, is referred to at paragraphs No.32 - No.34, to explain what was laid down therein. The court has held that in Cheran Properties the Group of Companies doctrine was interpreted to hold that its true purport is to enforce the common intention of the parties where the circumstances indicate that both the signatories and non-signatories were intended to be bound.

In Ameet Lalchand supra, referred to at paragraph No. 35, it is explained that the said judgment had relied on Chloro Controls to hold that a non-signatory, which is a party to an interconnected agreement, would be bound by the arbitration clause in the principal agreement. And that in view of the composite nature of the transaction, the disputes between the parties to various agreements could be resolved effectively by referring all of them to arbitration.

In Reckitt Benckiser supra, referred to at paragraph No. 36, certain additional factors for the invocation of the Group of Companies doctrine were said to be identified. Namely, the participation of the non-signatory party in the negotiation and performance of the underlying contract was held to be the key determinant of the intention of the parties to be bound by the arbitration agreement.

In C a n a r a Bank supra, referred to at paragraph No. 37, it was said to be noted that the Group of Companies doctrine could also be invoked "in cases where there is a tight group structure with strong organisational and financial links, so as to constitute a single economic unit, or a single economic reality." The last in the above series of cases, which was said to be a 3-Judge Bench decision, in Discovery Enterprises supra, referred to at paragraph No.38, is said to have held that in addition to the cumulative factors laid down in Chloro Controls, the performance of the contract was also an essential factor to be considered by the Courts and tribunals to bind a non-signatory to the arbitration agreement.

14. After a thorough discussion on the points of law the Constitution Bench has recorded the following Conclusions, at paragraph 165, thus:

a. The definition of "parties" under Section 2(1) (h) read with Section 7 of the Arbitration Act includes both the signatory a s well a s non-signatory parties;

b. Conduct of the non-signatory parties could be an indicator of their consent to be b o u n d b y t h e a r b i t r a t i o n a g r e e m e n t ;

c. The requirement of a written arbitration agreement under Section 7 does not exclude the possibility of binding non- signatory parties;

d. Under the Arbitration Act, the concept of a "party" is distinct and different from the concept of "persons claiming through or under" a party to the arbitration a g r e e m e n t ;

e. The underlying basis for the application of the group of companies doctrine rests on maintaining the c o r p o r a t e s e p a r a t e n e s s of the group of c o m p a n i e s while determining the c o m m o n intention of the parties to bind the non-signatory party to the arbitration agreement;

f. The principle of alter ego or piercing the corporate veil cannot b e the basis for the application of the group of companies doctrine;

g. The group of c o m p a n i e s doctrine has an independent existence a s a principle of law which s t e m s from a h a r m o n i o u s reading of S e c t i o n 2(1)(h) a l o n g with Section 7 of the Arbitration Act;

h. To apply the group of companies doctrine, the courts or tribunals, as the case may be, have to consider all the cumulative factors laid down in Discovery Enterprises (supra). Resultantly, the principle of single e c o n o m i c unit c a n n o t b e the sole basis for invoking the group of companies doctrine;

i. The persons "claiming through or under" can only assert a right in a derivative capacity;

j. The approach of this Court in Chloro Controls (supra) to the extent that it traced the group of companies doctrine to the phrase "claiming through or under" is e r r o n e o u s a n d a g a i n s t t h e w e l l - e s t a b l i s h e d p r i n c i p l e s o f c o n t r a c t l a w a n d corporate law;

k. The group of companies' doctrine should be retained in the Indian arbitration jurisprudence considering its utility in determining the intention of the parties in the context of complex transactions involving multiple parties and multiple a g r e e m e n t s ;

I. At the referral stage, the referral court should leave it for the arbitral tribunal to decide whether the non-signatory is bound by the arbitration agreement; and

m. In the course of this judgment, any authoritative determination given by the Court pertaining to the group of companies' doctrine should not be interpreted to exclude the application of other doctrines and principles for binding non- signatories to the arbitration agreement.

One of the Hon. Judges of the Bench, while concurring with the above opinion passed a separate judgment to additionally, conclude thus:

I. An agreement to refer disputes to arbitration must be in written form, as against an oral agreement, but need not be signed by the parties. Under Section 7(4)(b), a court or arbitral tribunal will determine whether a non- signatory is a party to an arbitration agreement by interpreting the express language employed by the parties in the record of agreement, coupled with surrounding circumstances of the formation, performance, and discharge of the contract. While interpreting a n d constructing the contract, courts or tribunals may adopt well-established principles, which aid and assist proper adjudication and determination. The Group of Companies doctrine is one such principle.

II. The Group of Companies doctrine is also premised on ascertaining the intention of the non-signatory to be party to an arbitration agreement. The doctrine requires the intention to be gathered from additional factors such as direct relationship with the signatory parties, commonality of subject-matter, composite nature of the transaction and performance of t h e c o n t r a c t .

III. Since t h e p u r p o s e of inquiry by a court or arbitral tribunal u n d e r Section 7(4)(b) a n d the Group of C o m p a n i e s doctrine is the s a m e , the doctrine c a n b e s u b s u m e d w i t h i n S e c t i o n 7(4)(b) to e n a b l e a c o u r t or a r b i t r a l tribunal to determine the true intention a n d c o n s e n t of the non-signatory parties to refer the matter to arbitration. The doctrine is subsumed within the statutory regime of Section 7(4)(b) for the purpose of certainty and systematic d e v e l o p m e n t of law.

(iv) The expression "claiming through or under" in Section 8 and 45 is intended to provide a derivative right; and it does not enable a non- signatory to become a party to the arbitration agreement. The decision in Chloro Controls (supra) tracing the Group of Companies doctrine through the phrase "claiming through or under" in Section 8 and 45 is erroneous. The expression "party" in Section 2(1)(h) and Section 7 is distinct from "persons claiming through or under them". This answers the remaining questions referred to the Constitution Bench.

15. In the light of the clear exposition of law by the Apex Court as above, it is a mere exercise of applying t h e t e s t s p r e s c r i b e d , to c o n c l u d e w h e t h e r a n o n - s i g n a t o r y, to the arbitration agreement, could yet be subject to arbitration. To wit, whether R-2 in the case referred to above, a non-signatory to the arbitration agreement, could yet be made a party to the arbitration proceedings. A closer examination of the facts reveals the following:

The MoU between the Claimant and R-1, which formed the basis of the arbitration, had no reference to R-2. However, it is seen R-1 was an agreement- holder under registered agreements, of several identified items of land. It is also found that R-1 had also e x e c u t e d A s s i g n m e n t D e e d s in favour of third- p a r t i e s a n d a l s o h a d a c t e d a s a Confirming Party, in his capacity as an erstwhile agreement holder, to registered Sale Deeds executed by the landowners in favour of R-2, thereby apparently permitting and confirming the said transactions. In both the above sets of transactions the lands identified in the MoU between the Claimant and R-1 are seen to be found. Hence, R-1 had wilfully concealed the said transactions from the Claimant.

16. To apply the law as laid down in Cox & Kings (supra) to the facts of the case, stated briefly above:

i) "The definition of "parties" under Section 2(1)(h) read with Section 7 of the A & C Act includes both the signatory as well as non-signatory parties"

In the case on hand the "parties", would not only be the claimant and R-1, the signatories to the arbitration agreement, but even R-2, a non-signatory - depending on other factors, as examined below.

ii) "Conduct of the non-signatory parties could be an indicator of their consent to be bound by the arbitration agreement"

iii) "The requirement of a written arbitration agreement under Section 7 does not exclude the possibility of binding non-signatory parties"

iv) "Under the Arbitration Act, the concept of a "party" is distinct and different from the concept of "persons claiming through or under" a party to the arbitration a g r e e m e n t ;

V) "At the referral stage, the referral court should leave it for the arbitral tribunal to decide whether the non-signatory is bound by the arbitration agreement;"

In the present case, it is seen from the contents of the Assignment Deeds and the Sale Deeds, to which R-1 is a party, the properties which are the subject matter of the Mou, between the Claimant and R-1 - and the properties involved in those former referred transactions are some of the very items of property covered under the MoU. The conduct of R-2 is certainly conduct which may be construed as an indicator to be bound by the arbitration agreement, found in the MoU.

The inclusion or non-inclusion of non-signatory party or parties, at the referral stage makes no difference, for an arbitral tribunal to implead a party to the arbitration proceedings.

vi) "The Group of Companies doctrine is also premised on ascertaining the intention of the non-signatory to be party to an arbitration agreement. The doctrine requires the intention to be gathered from additional factors such a s direct relationship with the signatory parties, commonality of subject-matter, composite nature of the transaction, and performance of the contract"

In the case on hand, the Assignment Deeds referred to, were executed a few months prior to the MoU - and thus it is clear that R-1 had suppressed the fact to the Claimant. And the Sale Deeds, referred to above were subsequent to the MoU- again displaying concealment of the prior transaction in favour of the Claimant.

Therefore, it is clear that there was a direct relationship between the Claimant and R-1 as regards the arbitration agreement. The subject properties of the MoU and the portions covered under the Assignment Agreement Deeds and the Sale Deeds, referred to above, provide the commonality of subject-matter. The fact that the intention of the Claimant was to develop, what were transacted as two portions of lands, the second portion to provide access and a frontage to the other larger portion of lands to be developed, would qualify as the composite nature of the transaction. In that, any dislocation of the composite scheme - of developing the larger portion of lands with the utility and use of the lesser portion, would possibly affect the overall development.

vii) One significant point raised by R-2, was that, irrespective of the inclusion of R-2 in the earlier proceedings preceding arbitration, a notice under Section 21 of the A &C Act was a prerequisite for an arbitral tribunal to exercise jurisdiction on R-2.

Reliance is placed on the judgment of the Apex Court in the case of M/s Adavya Projects Private Limited v. M/s Vishal Structures Private Limited (Civil Appeal No. 5297/2025 vide Order dated 17.04.2025). To contend that, R-2 not being a signatory to the MoU, which document is said to contain the arbitration clause, and there being no privity of contract with the Claimant, and the court proceedings for appointment of the arbitral tribunal also having been brought only against R-1,- R-2 could not be arrayed as a party to arbitration.

However, it is seen that the very judgment, referred to above, states that it does not preclude a party to rope in a non-signatory to arbitration. And the arbitral tribunal is competent to bind a non-signatory- if his conduct demonstrates consent and that the "veritable party" test, active involvement in negotiation or performance, receipt of benefits, and alignment of conduct. R-2's newspaper publications of a proposed sale of portions of the subject property and the subsequent sale deeds, confirm that R-2 actively asserted title and benefitted directly from transactions in respect of portions of the subject property.

In Adavya (supra), the Apex Court has referred to the factors laid down in Discovery Enterprises (supra) which are held to be holistically considered to determine whether or non-signatories are parties to the arbitration agreement, which is quoted below:

"40. In deciding whether a company within a group of companies which is not a signatory to arbitration agreement would nonetheless be bound by it, the law considers the following factors:

(i) The mutual intent of the parties;

(ii) The relationship of a non-signatory to a party which is a signatory to the agreement;

(iii) The commonality of the subject-matter;

(iv) The composite nature of the transactions; and

(v) The performance of the contract."

It is to be noted that, Adavya (supra), does lay down as to 'what' is to be proved in a given case, while the judgment in Cox & Kings (supra) and a decision of the Hon. High Court of Karnataka in M/s Devtree Corp. LLP v. M/s Bhumika North Gardenia, MFA 2978/2024, dated 24.07.2024, expound on 'how' it is to be proved. These judgments establish two independent pathways to party status for a non-signatory.

Firstly, under the principle of derivative rights in Devtree (supra), a non-signatory "claiming through or under" a signatory, such as a successor or assignee, inherits the obligation to arbitrate along with the rights.

Secondly, as clarified by the Apex Court in Cox & Kings (supra), a non-signatory's deep and invasive involvement within the subject-matter of the dispute and the performance of the contract demonstrates an implied consent to be bound, making it or him a "veritable party".

Both the above pathways lead to the s a m e conclusion required by Adavya (supra). The Apex Court has affirmed that an arbitral tribunal's kompetenz- kompetenz to conduct such a fact-based analysis.

In the result, the arbitral tribunal, in the above case, had allowed R-2- above referred, to be impleaded as a respondent in the arbitration Claim.

Justice (Rtd) Anand Byra Reddy

Formerly of the High Court of Karnataka