S Basavaraj, Senior Advocate, Member Karnataka State Bar Council.

Did you read the viral “Open Letter to My Fellow Citizens and the Management of IndiGo” written by an IndiGo pilot? The letter starkly exposed the systematic implosion of an institution. The letter is a first-hand account by an IndiGo employee. It explains that the airline’s current crisis did not arise overnight; it was the result of years of unchecked arrogance, aggressive expansion, and the belief that IndiGo was “too big to fail.” Employees repeatedly warned of systemic problems, even as the airline was celebrated publicly and competition was steadily eliminated. Internally, the institution deteriorated as power and titles overtook merit. Employees at every level—pilots, engineers, ground staff, and cabin crew—were overworked, underpaid, and silenced through fear and humiliation. Fatigue concerns were ignored, manpower was cut, and workloads increased without compensation. The consequences are now visible to the public. Service quality has declined not due to lack of care, but because exhausted employees are running on empty. Regulatory oversight failed to protect workers, leaving them without representation or relief. The author appeals to the government for fair wages, humane fatigue rules, and accountability, warning that IndiGo will not collapse from treating its employees fairly—but it will if it continues to treat them as expendable.

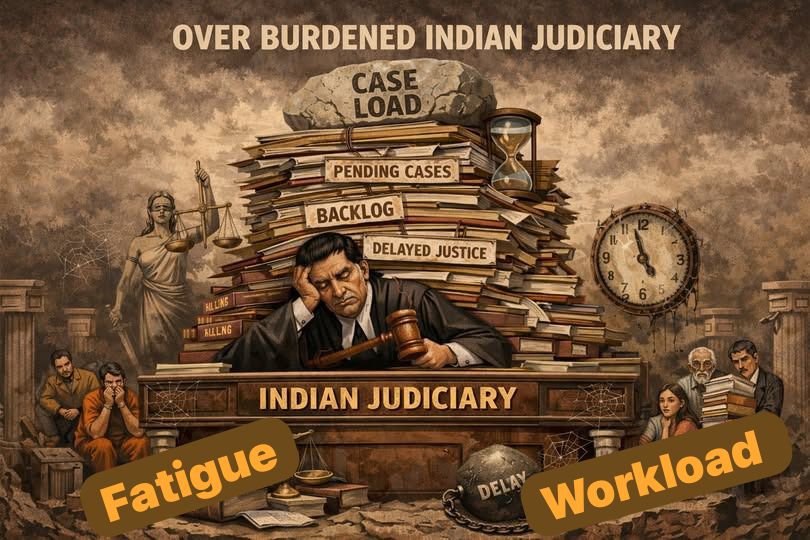

So here’s my take on the Indian judiciary on the similar lines.

Yesterday, 16 December 2025 we, the members of the Karnataka Bar, assembled in a General Body Meeting to discuss the proposal of the Chief Justice of Karnataka to make two Saturdays in a month sitting days to “increase disposal of cases.” Many of us opposed the proposal—not because we are unwilling to work, but because the idea is flawed and counter-productive.

Many judges dispose of cases on working days by passing short orders or by simply stating, “petition allowed,” “quashed,” etc. On Saturdays, they usually complete the order or judgment by dictation. If judges are required to work on Saturdays, such dictation would take place in open court, thereby consuming the entire day only for dictation. The end result would remain the same.

The condition of our judiciary is no longer an internal institutional concern. It affects every citizen who waits for justice, sometimes for decades.

The crisis of the Indian judiciary did not emerge suddenly. It is the result of years—decades—of neglect, complacency, and misplaced priorities.

At independence, we inherited a judicial system designed for a colonial population and a limited docket. Over time, democracy deepened, rights expanded, litigation multiplied, and expectations rose. But the system itself did not evolve at the same pace. Court buildings remained the same, sanctioned strength of judges lagged behind population growth, and procedural reforms moved at a glacial pace.

With one more judge Justice Mudagal retiring this month, the vacancy in the Karnataka High Court has gone upto 14. There is not a single direct appointment of judges to Karnataka High Court in the last 4 years. The collegium is almost non-functional when it comes to choosing eligible candidates.

The sanctioned strength of the Karnataka High Court is 62 judges; however, only 49 judges are presently in position. In reality, the Court requires at least 75 judges and around 100 court halls to function effectively. The existing judge strength and infrastructure are grossly inadequate and in a deplorable state.

Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation have brought about a paradigm shift in the country, generating an unprecedented volume of litigation that demands a robust judicial infrastructure and a substantially higher number of judges. Karnataka alone has over 1,25,000 lawyers—more than sufficient to meet professional requirements. However, at the level of the judiciary, the situation remains dismal. Judges and lawyers work as a team to clear the huge backlog.

We thought our system of judiciary is great in all aspects. Yet, year after year, the warning signs were ignored. Mounting arrears were normalised. Vacancies were explained away as “temporary.” Overburdened judges were praised for disposing of thousands of cases instead of being supported with systemic solutions. Like many institutions before collapse, the judiciary continued under the comforting illusion: “We are too essential to fail.”

The Indian judiciary today suffers not from lack of dedication, but from chronic overwork and under-support.

Judges routinely handle causelists that no human being can meaningfully absorb. Trial court judges hear dozens—sometimes hundreds—of matters in a single day. High Court judges grapple with thousands of pending cases, often without adequate research assistance, clerical support, or infrastructure. Vacancies force existing judges to shoulder the burden of empty courtrooms.

Court staff—clerks, stenographers, process servers—work with outdated systems, minimal training, and little recognition. Many are responsible for work that should be handled by multiple hands. Files move slowly not because of indifference, but because the system is stretched thin at every seam.

And like the exhausted airline crew smiling through fatigue, judges and staff are expected to project efficiency, authority, and composure—while operating under crushing pressure.

When judges raise concerns about workload, infrastructure, or manpower, the response is rarely urgent. There are no consequences for delay in appointments, no accountability for administrative apathy. Instead, the narrative subtly shifts: “Judges should work harder.” As if justice were an assembly line.

How Do You Expect Justice When the System Itself Is Exhausted?

We often blame delays on lawyers, litigants, or “frivolous cases.” Rarely do we confront the uncomfortable truth: a system designed for far fewer cases cannot cope indefinitely with exponential demand.

When judges are overworked, the quality of adjudication inevitably suffers. When court staff are understaffed, procedural delays multiply. When infrastructure is inadequate, hearings are postponed, files are lost, and litigants lose faith.

Justice is not delayed because judges do not care. It is delayed because they are asked to do the impossible—every single day.

And Then There Is the State

Judicial independence is constitutionally celebrated, but administrative dependence remains real. Appointments are delayed. Infrastructure funding is uneven. Technology is introduced without adequate training or ground-level consultation. Reforms are announced, but implementation is half-hearted.

There is no strong, institutional mechanism where judges and staff can collectively articulate their concerns without fear of being perceived as “complaining.” Like many essential services, the judiciary is expected to function silently, efficiently, and endlessly—regardless of the human cost.

Where We Are Today — A Crisis We Pretend Is Normal

Crores of cases are pending. Litigants spend the best years of their lives waiting for closure. Judges burn out quietly. Court staff retire without ever seeing meaningful reform.

And yet, we continue to act surprised when confidence in the justice system erodes.

The truth is uncomfortable: the Indian judiciary is running on exhaustion and goodwill. It survives because of the commitment of its people, not because the system supports them adequately.

If justice is truly the foundation of our democracy, then the judiciary cannot be treated as an afterthought. What is urgently needed is not rhetoric, but action:

• Filling judicial vacancies within fixed timelines

• Adequate staffing and fair working conditions for court personnel

• Realistic case allocation and scientific workload assessment

• Modern infrastructure and meaningful technological support

• Administrative accountability for systemic delays

The judiciary will not weaken because it is supported.

It will weaken if it continues to be taken for granted.

Let This Be a Turning Point

I still believe in the Indian judicial system. I believe in the integrity of its judges, the dedication of its staff, and the promise of justice enshrined in our Constitution.

But belief alone cannot sustain an institution forever.

Like every system built on human effort, the judiciary needs care, reform, and respect for those who keep it running. Silence, exhaustion, and denial are not signs of strength—they are warning signals.

And this time, we should listen.